I've been waiting since December 2009 to talk about this, and until now I've been pretty good at keeping everything secret. My new documentary premiered tonight on Ovation TV, which means I can post this blog about it. So, the first thing is to announce where you can buy it so you can watch yourself, and the second is my journal / blog about the entire trip.

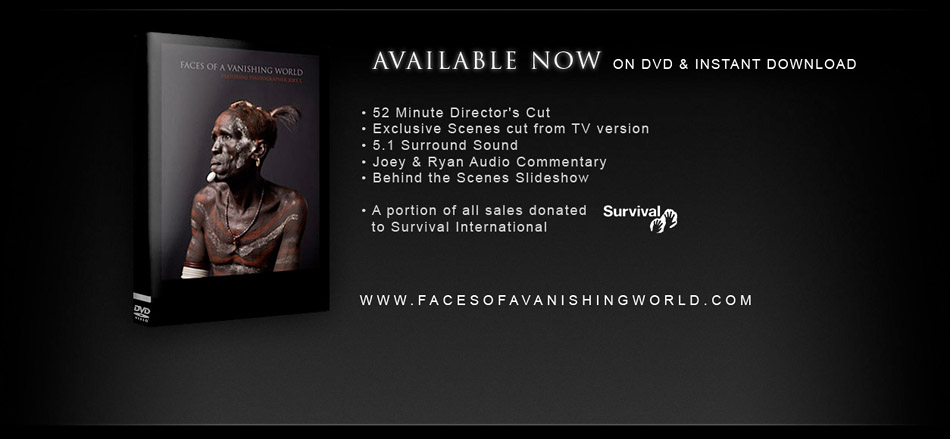

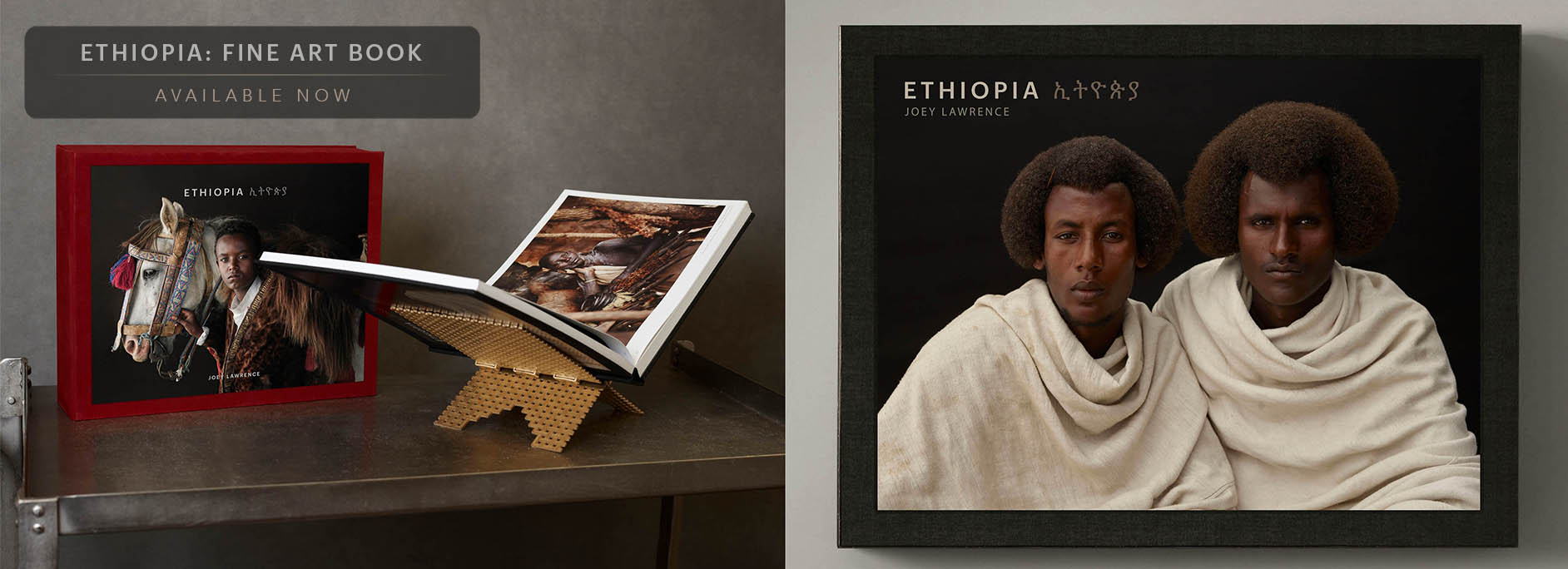

The documentary is available through my site to purchase on both DVD (costs only $25) or as an instant download ($20). I hope this is a nice break for the people used to paying the higher prices for my educational tutorials. I think this one should be full of just as much knowledge, but in a different way. The official trailer for the documentary is above. I am also donating a portion of all sales to Survival International, who are supporting the tribal people of the Omo Valley defend their rights, protect their lands and determine their own futures. The store page explains everything included in the documentary, so check that out if you’d like to find out more. The first 500 copies sold will be personally signed in silver ink, so if you want one you better act fast!

THE JOURNAL: PRELUDE

Our 4×4 is tearing down a dusty road somewhere in the South of Ethiopia. It’s all familiar. Out the window are pillars of rock and mountain, blanketed in layers by a dense sand storm in the distance.

Ryan is asleep beside me. Anteneh is awake but deep in thought, watching the landscape in which he grew up pass by outside the window.

It’s been exactly a year since we’ve all been back together here, en route to the Omo Valley. This is a place that doesn’t seem to exist at all once you leave, it doesn’t seem believable when you’re at home.

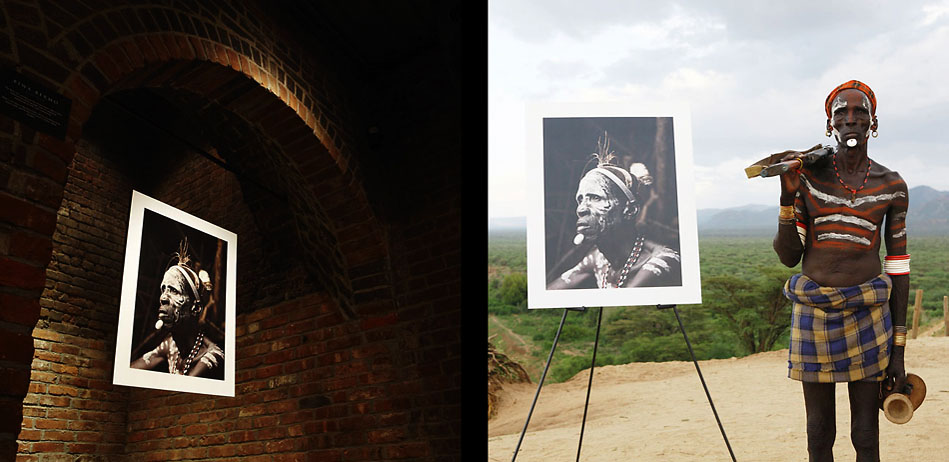

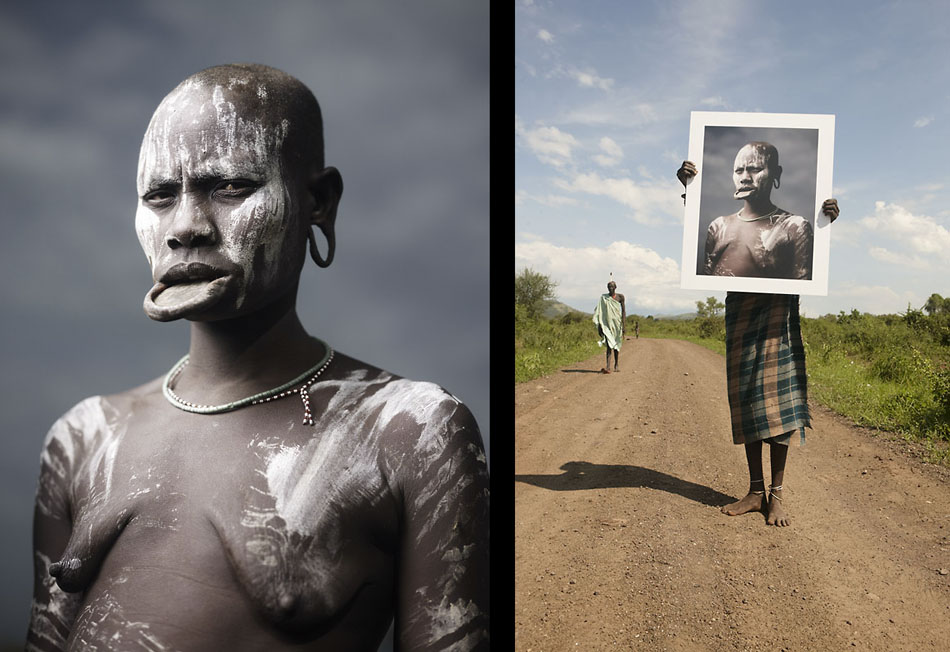

What brought us to Ethiopia the second time was different from the first. Ovation TV, an arts and entertainment channel in the US, had financed a television pilot. (Later on, the documentary will be syndicated by National Geographic.) It’s a sort of documentary based around my life, photo shoots and travels. I co-created, wrote and “starred” in the pilot. When the initial discussions with the network arose, I knew that we had to go back to Ethiopia for the episode. I’ve always wanted to return and do this huge installation, returning large prints of portraits to the subjects I photographed to their own land. So when a gallery installation in New York I had came to a close, I knew it was an auspicious time to remove the prints from the walls, somehow get them with me to Ethiopia. The network was also cool about it, and put enough trust in us to do our thing.

The installation in New York…

…the installation in the Ethiopian tribal lands

The installation in New York…

…the installation in the Ethiopian tribal lands

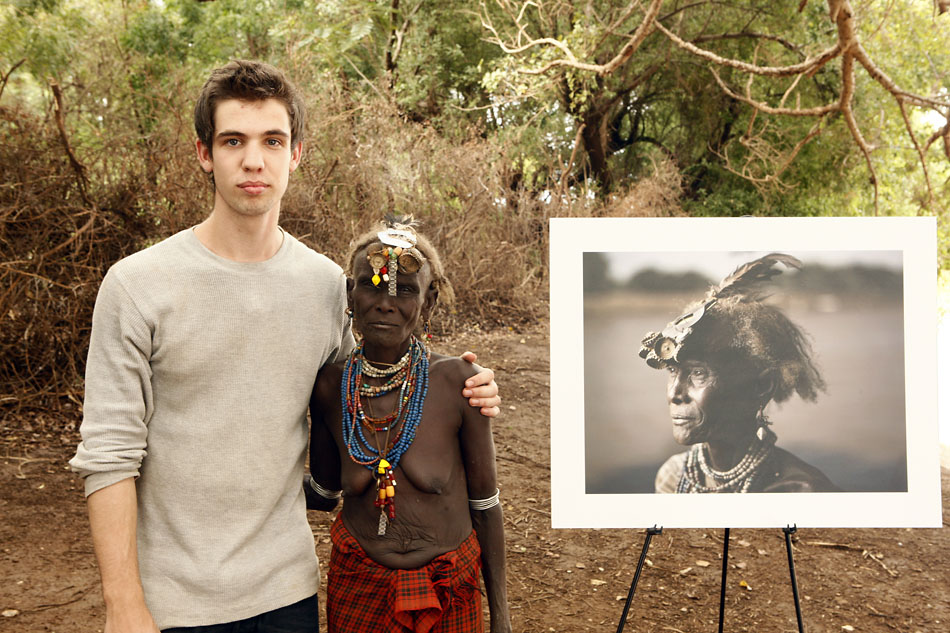

I’ve always believed that my photography is a collaboration between the subject and myself. What I do is not a simple matter of going and snapping pictures. I feel if there’s one thing that separates my work, it’s the mindset. The tribes of the Omo Valley never really understood photography, even if they did trust me and decide to pose for me. “What’s a white boy coming all the way here for, just to have a copy of our likeness? Is this just what the faranji do?” This project would be a way to share what I do. It was more of a personal sociological experiment than it was a charity, and the results I will remember for the rest of my life.

The tribes of the Omo Valley are changing at a rapid rate. These cultures are on the brink of extinction. Their traditions, language and beliefs are threatened to be lost forever as they are assimilated, acculturated or swallowed into the larger groups of the cities and towns. By giving someone their portrait, you instill a sense of cultural integrity … a sense of connection to heritage, to the ancestors.

It doesn’t mean that they can’t be part of the modern world, change is inevitable. In fact, any ethnic group alive today is the product of generations of cultures clashing and intermixing. These prints are simply a reminder of identity.

The biggest difficulty of the trip would not be getting the prints delivered, navigating the unforgiving roads and paths, or the break out of tribal war. The hardest part would be dealing with the other 4×4 behind ours.

In that other vehicle was a film crew, attempting to document exactly what it is that I do.

Dec 3rd, 2009

I had spent the last days before Ryan and I’s flight trying to get a bunch of work done. It was crunch-time. It seems like this is always the case before I leave for a long trip. The reason why I can usually sleep on long flights is because I’m so deprived of sleep before I go. This time it was 3 hours of rest in two days.

Anteneh had called my cell phone and warned us that a tribal conflict had escalated in the South of Ethiopia. The Daasanach were in a bitter battle with the Hamer, and it may not be the best time to go. We gave it some time, and had to reschedule the trip a week later when things simmered down. When we left, there was still conflict on the borders but the chiefs had gotten together to find a resolution.

Our flight was a long one. We flew from New York City to Toronto, and literally spent all day trying to get our bags as cheap in overweight charges as possible at the KLM desk.

Our episode was shot on a tight budget, and every nickel and dime counted. Puppy dog eyes work every time at the airline counter.

NYC > TORONTO > AMSTERDAM > KHARTOUM > ADDIS

In Amsterdam we had enough time to leave the airport and grab a bite to eat in the city center. In Khartoum we just stayed on the plane, both miserable and anxious.

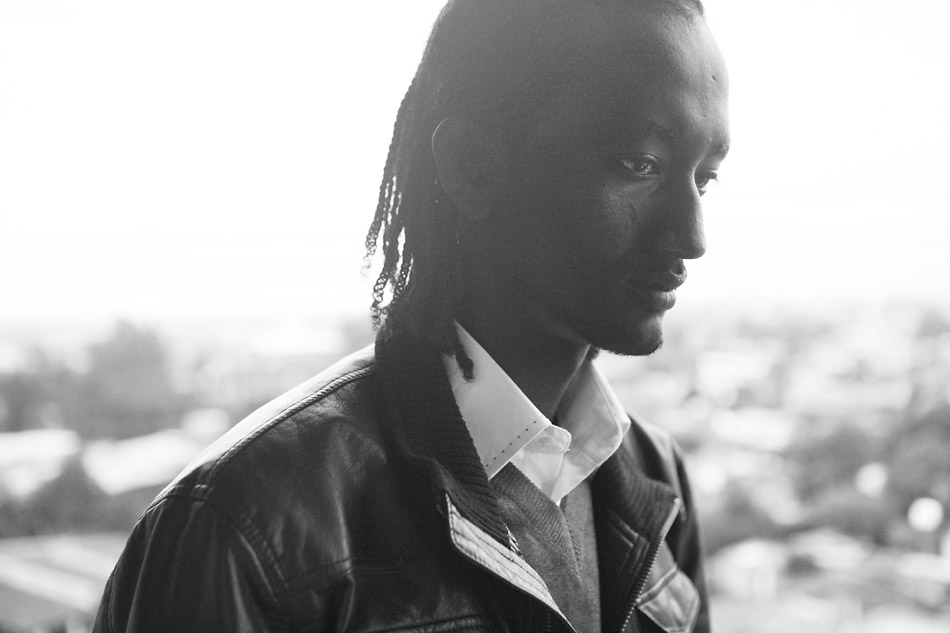

The main thing that I was excited for in this trip was seeing Anteneh again. I consider him one of my best friends and I believe a friendship is not based on time, but the shit you’ve been through together. When we arrived at the Addis Ababa Bole airport, my hands were shaking. I’m not sure if it was out of the nervousness of seeing a friend I hadn’t seen in a year, going through customs with all my photo gear, or simply a result of jet lag and getting toasted on the plane. I guess it was a combination of all of those.

Our first sight of Anteneh was that out of a movie. We ran our carts up to him, jumped off them while sliding and gave him a huge bear-hug. He was holding a sign for us which read:

“PUSSY MONEY WEED CREW! BACK IN TOWN”

Charming.

The feeling of being there in the airport with Ryan and Anteneh again the same way we had 1 year ago was other-worldly. Later, we ate at “Champions.” This is one of our favorite places in Addis.

I looked at both of my friends in the eyes and told them “guys… there is no where else in the world I’d rather be. There’s nothing else I’d rather be doing then hanging here with you guys in Ethiopia.” I meant it, and it was straight from my heart. I was getting sentimental as fuck and wasn’t even on my second St George.

A lot has changed in Anteneh’s life since we left him last year. His life was messed up, full of unanswered questions.

My blog post had brought him countless new business of photographers wanting to explore the Omo Valley. He was able to support himself and keep his sisters in school. Now, before you think I am taking credit for his success, I am not. Anteneh is good at what he does. It was his skills that brought the clients, my blog simply gave him the platform to reach a larger audience, and I thank those who have trusted his skills. Now with the show, I expect things to go a little crazy for him. Here is how to get in touch with him- www.facebook.com/pages/Visions-of-Ethiopia-Tours/453321391412619

In Addis we stay in the area of Hiyolet. It has a certain sense of life at night, and I suppose it’s the “dodgy” area of the city. Little shack bars lit up with Christmas lights dot the main strip, and drunks mix with beggars and street children. There are girls everywhere, 100% of which are prostitutes. There’s a reason they think you’re so handsome, they want in your pockets.

Dec 4th, 2009- ETHIOPIAN BAR BRAWL, THE STUFF YOU DON’T SEE ON TV

Ryan is a little under the weather and couldn’t eat much. I think the long flight has caught up with him, so he’s laying low for today. Anteneh and I spent the day exploring Addis like the good ‘ol days. At night, things turned to complete shit.

While Ryan rested, Anteneh and I went out to a bar called Harlem Jazz. It’s known to be a chill place, with some live music and friendly atmosphere. It’s near the airport- we were waiting to pick up a few of the camera crew from Toronto that hadn’t arrived yet. On our way out of the bar, we saw two Japanese guys getting mugged. They were jumped by a gang of Ethiopians aged 20-25. I’m not sure what they had done earlier, but the gang surrounded them, making threatening pushes and slaps to the head.

Anteneh stepped in, trying to break up the fight. The gang then surrounded Anteneh and they started to scream at each other in Amharic. The shit hit the fan when one of the gang pushed Anteneh, then our friend the Hamer Warrior punched him back in the head.

Punches began being thrown on all sides. I stepped in at this point, punching two of them in the face and got punched and kicked a few times myself. The size of the mob escalated, and soon there was an out of control brawl unfolding. Things got out of hand. An Ethiopian grabbed an enormous rock and smashed it against one of the Japanese guys head. He dropped to the ground. There was so much blood we thought he had gotten stabbed.

Eventually, after Anteneh getting wacked in the head with a stick, we managed to get the Japanese guys to the hospital with the help of George- another Ethiopian friend of ours. At this point, Anteneh’s adrenaline had faded, and he began to feel the pain in his head. We were over 45 minutes late arriving at the airport. Anteneh was now too messed up leave the car so I ran inside. I went through security and set off toward the arrival gate, shoes not on feet yet. The crew had just gotten off the plane and I put on my “people voice” trying to sound as normal as possible. When the small talk finished, I turned to the director, Blair, alone and said “we need to talk….”

I’ve never considered Addis Ababa a dangerous place, so I was upset that this was the first notion the crew had gotten of this beautiful country.

THE BLACK MARKET

Before hitting the road, we have a few things to take care of in Addis. A generator and a car battery so I can store energy from my solar panel. The main objective for today was changing our American money into Ethiopian BIRR. There’s not exactly ATM’s where we are going, and if you want to try and swipe a credit card, you’re best doing it in your ass.

Dec 7th 2009

We are finally on the road, I’m writing from our 4×4. Today we left Addis to Arba Minch. We were delayed by two days because Anteneh was in bad condition from the fight. The morning after, he woke up puking, a very bad sign. So we took him to the hospital for a brain scan. We were all extremely anxious sitting in the waiting room, watching our friend slowly being pulled into the brain scan machine. But the scan projected there were no fractures, no internal bleeding or swelling. Just problems on the outside of the skull that would heal in a few days.

The next morning Anteneh needed at least one more day of rest, so we spent the day driving around Addis getting B-roll. Anteneh met up with us later that day and helped us around the city. He was tired still, but back to his old calm self. Our friend was finally back.

So after a full days drive to Arba Minch, we arrived at the hotel. None of the power worked in the entire city. We tip-toed carrying our heavy equipment and after dinner went straight to bed.

Dec 8th, 2009

A new road has shaved a whole day of driving off. Last year it took 3 days to drive to the “gateway” of the Omo Valley, a small town called Turmi. This time it only took two.

This drive has always been my favorite because of the subtle gradiation you notice in both people and landscape. The people change with the landscape, from the city dwellers of Arba Minch, then Oromo farmers, then the Gamo, darker in skin, then the tribal lands come into view- the Konso, the Tsemay, and finally the Arbore.

Along the road a dust storm up ahead stops the car, and we get out to take some footage.

Ahead I spot the silhouette of a man walking towards the cars. As he comes closer, I notice his jewelry and decoration, marking him as part of the Hamer tribe. They wear as many earings as they have wives, their scarification is in neat rows representing enemies killed in battle, and their skin is medium brown. As the man gets closer, I realize his hand is severely bleeding.

The tribes of the Omo Valley are heavily armed because they have been at war with each other for hundreds of years. The difference is now the AK-47 replaces the spear or bow and arrow. Each tribe occupies their area of fertile land, which can only support so many crops or so much land to roam their cattle on. Cattle is the economic currency of the south, and raiding is common.

His son had accidentally shot him, leaving a hole between the flesh of his two fingers. A lucky strike. The tissue seemed to be oozing out. In the show a lot of this had to be cut because it was too gruesome for television. Anteneh, Ryan and I quickly elevate the arm, and fix his wound with water, disinfectant, then a gauze and tape to keep pressure on the wound. The Hamer man was calm the entire time, and thanked us at the end.

All the while this was going on, another set of action was unfolding. Audio and video were not prepared, and it took awhile to get them rolling. They should be ready at all times, if they wish to make a real documentary. The director tensed up under the pressure and couldn’t make calls. This kind of situation is serious, but of course happened upon us, so it needs to be documented. I get in a big fight with the director and curse the way he handled the situation. We eventually make up and move on- everyone is doing a good job and is on the same team anyway, and this situation was completely unexpected.

Dec 9th and 10th

Last night we arrived in Turmi, the small village at the gateway to the tribal lands. It serves as a meeting ground for many Hamer, who come to sell their farming goods to each other at the market.

It was the weirdest feeling looking at our old hotel, Mentesenote. It was like being in a movie, starring at this mud building that only seemed to exist in my memories. The keeper girl recognized us and wondered why we were back. Ryan and I sat inside the little room in silence. It was good to be back.

THE KARO

After a night in Turmi we set off to the Karo tribe. The plan was to spend a few days with them and then go on to the village Anteneh grew up in the Hamer tribe.

It’s important to keep in mind that whenever I mention “road” in this journal, it’s not necessarily the description of a road you are used to. The “road” to the Karo is simply a mud path, terrible to drive on, and frequently interrupted by pools of mud, boulders, and rivers.

Upon arrival at the Karo village, we searched for the chief. We would have to ask him permission for the film crew. Anteneh and I searched for the chief but learned that he was gone to help sort out the war between the Daasanach and the Hamer. Left in his stay was the chiefs son Boneh, who’s name translates to “drought.”

At first he was trusting to us because of last year, but not sure about the film crew. He had been screwed over before, the Karo had been filmed by the BBC before and exploited, ripped off. So I decided to take out one of the prints, and tell him what we wanted to do. That made all things a go, and I told him to stay quiet about what we were going to do with the pictures taken last year. He agreed with a smile.

Ryan, Anteneh and I explored the village while the film crew did their own thing, we saw a lot of familiar faces and they saw us, taking our hands and wondering why we had come back. The Karo have a spectacular view of the Omo River. We went down to the riverbed to take some portraits. All of a sudden, we heard a familiar grunt from the top of the river bank. It was our friend Biwa, who we had photographed in that same spot 1 year before.

As an elder of the Karo, Biwa is respected and well adorned as a warrior, carrying rows of scarification representing the enemies he killed in battle. Biwa even fought the Mursi, who are said to be some of the most fierce warriors in Africa, and threw them out of the land his tribe now occupies. There are only around 1000-1500 Karo, these are the only surviving keepers a language, culture and complex belief system. The Karo are the most endangered tribe of the Omo Valley.

Biwa is a lot different from most of his brothers. He carries himself differently, and seems to always have this warm presence about him. He loves to sing and dance at night, and when he walks through the village the children chant “Biwa! Biwa! Biwa!”

I spoke a bit with Biwa through Anteneh’s translation, then settled in for the night in one of the huts. It was an interesting night’s sleep through a rainstorm, but it was good to be here in the middle of it all.

Our audio man Val lost his toothpaste. He exclaimed angrily that had to brush his teeth with something, so he opted for shaving cream, scowling the entire time and cussing at his misfortune.

THE FIRST REVEAL

I remember being so nervous about how the tribes would react to their photographs. Surely they are not completely sheltered and shut off from the outside world, they’ve met with visitors and even seen their images on the backs of digital cameras. Some of the girls have little mirrors, or check their reflection in the mirror of our 4×4.However, they’ve never seen an image of themselves printed this big. If they look at the back of a digital camera they sometimes refuse to believe it’s them, because they are not the right size. The entire village gathered at sunset to the meeting place, which overlooks a breathtaking view of the Omo River. Ryan and I had set up the prints, and covered them with blankets so we didn’t ruin the surprise. I am not a showman in any way, but we had to think about the TV show and how this was going to work when we only had 1 main camera and 1 secondary camera to shoot on. We had to slow down the reveal in order to capture individual reactions, so we came up with the idea to pull off one sheet at a time. To me this seams a little bit cheesy and Survivor-style, but it was the only way to do it. Oh, and of course it built up significant tension and made the reveal much more fun for the Karo.

The first print to be revealed was of Magi, a young Karo mother. When I had taken her image one year ago, she was pregnant. She had been quite productive, and was pregnant again this year. When the sheet was pulled off, exposing the picture, all hell broke loose. Magi absolutely freaked out when she saw it, shouting and angrily storming away.

At this point I turned to Ryan. We were both horrified because we didn’t know what was going on. Internally, I was starting to regret even doing this project. I was asking myself questions- is this project ethical? is this a bad “experiment” that I should have never thought of? Have I damaged this woman’s sense of pride?

Later on, we found out what happened. You see, Magi had never seen an image of herself that big. Just as Karo men scar themselves with patterns symbolizing a taken life, the women scar themselves as a sign of giving life. Magi’s scarification is constantly being added upon with every child, it’s form of decoration to show womanhood and maturity. She also saw her scarification was different in the image, and this image was a kind of “portal” back in time, in which she saw herself pregnant with her previous child. The birth had been full of complications, although the child was born safe. Magi was reminded of the dark time through the image.

The harsh questions I had asked myself earlier would eventually disappear that night. I was alone in a hut packing my camera equipment. A darks silhouette entered the hut. It was Magi. She looked at me, and motioned her hands in a square shape, the outline of a giant print. I gave her the image of herself. As soon as she had it in her hands, her eyes slid off of me, she jerked her head the other way, and quickly scampered away with her print. I guess she had wanted it after all.

The rest of the reveal after Magi had gone amazingly well, and reaffirmed my belief in the project. Damo Dori, a great conversationalist, had an extremely proud look on his face when he saw his portrait, but was shy and hid behind the crowd at first. Akeri, an elder shook my hand and wouldn’t let go. I wish I spoke the Karo language.

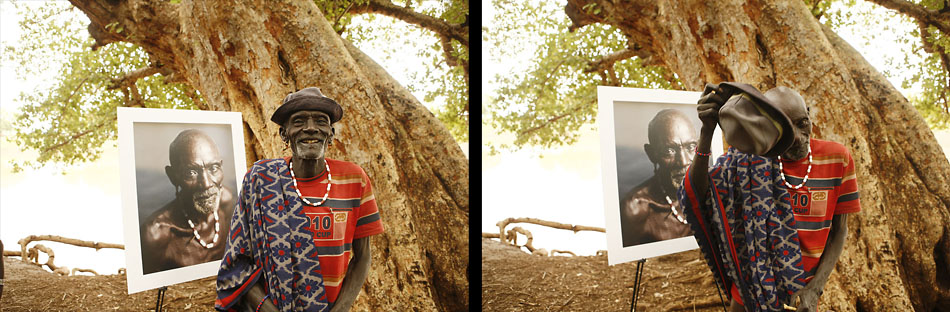

And last but certainly not least was Biwa’s print. Ryan and I had purposely saved his image for last because we wanted him to come and pull the sheet off himself. With every print before his, I watched Biwa applaud and cheer but he had a look of anxiety, as if he was hoping the next one would be his.

When Biwa revealed his print, you should have seen his face. First, he broke out in an enormous laugh. Then he started nodding at the picture, over and over. Then he decided to give it a little head-butt, perhaps to see what would happen. Biwa wanted to take it home right away, and he told me through Anteneh’s translation that he wanted to hang it in his hut. Biwa also asked to keep the plastic wrap, so it could be protected from smoke and the harsh climate.

Before departing New York, the prints were mounted on masonite and then sprayed with coat after coat of a protective matte finish by White House Custom Color (whcc.com). I imagine that print will still be out there in the South for years, protected and looking good as new, proudly sitting in Biwa’s hut. What Biwa and the others don’t realize is that they own the first of a limited edition run of prints made at that size. That’s the way I’d like to keep it.

SWOLLEN RIVER

The next tribe we plan to live with and give prints are the Hamer, in a village that Anteneh grew up in. The crew wanted a night to refresh, so we spent a night in Turmi, which is about 2-3 hours drive from the Karo with minor comfort- you can have a bed, a roof over your head, and really that’s the only difference.

I really don’t see the big difference between living with the tribes and Turmi. To me the tribes ventilated huts are much more comfortable than sleeping in a concrete box with a steal roof. We ate the same food as well- military rations of freeze-dried food. There are a few restaurants in Turmi, but they take forever to cook you anything and the food isn’t very pleasant. Not to mention the bonds and trust you make when you live with people. But hey- we are here filming a TV show so I’ll make sure the crew is comfortable… For now.

It has rained constantly for the last few days. Anteneh is worried that the upcoming roads in our trip might get impossible to navigate, or even to return to Addis. His worries come true when we leave early in the morning for his Hamer village. We approach a river bed we had crossed that was completely dry less than a week ago. Now a river has taken it’s place. The rapids thrash through the mud, turning the water a murky brown color. We get out of the car and access the situation…

“There’s no way we can cross this,” says our driver, Mengi.

I am adamant about delivering the prints. We have done tons of river crossings before. There are a line of cargo trucks on the other side of the river, waiting to cross as well.

“Anteneh, ask them how long they’ve been waiting for,”

Anteneh yells across the river in Amharic, “three days!” the drivers shout back.

I look at the river. It is laughing back at me, mouth foaming. I come to grips with the danger of crossing, and decide it’s best not to cross. Our crew gets together and has a conversation about what to do next. This road connects to the road leading back to Arba Minch, we are stranded. Another road around through Jinka is a practically a 3 day detour in this weather, our budget doesn’t allow that much time on the road.

Anteneh has an idea. “Joey, I know of another Hamer village we can get to. I visit them every time I’m down here.” When there was a Bull-Jump in the village a few months ago, Anteneh’s friend Bali walked to Turmi himself and found the call center. He gave the operator Anteneh’s cell phone number he had left with him before, and he called me to tell him about the ceremony. It was the first time he used a phone, and yelled into the receiver. Although we weren’t bringing any prints back, it was a great opportunity to take some time to myself for my photography. The crew agreed, so we headed in the direction of the village.

THE HAMER

What we found there was incredible. As soon as we trekked a little bit into the village, we were greeted with great enthusiasm. Usually the tribes are quite reserved in the Omo Valley before they know you, they see you as an outsider and treat you with caution. Generations of warring and living in a unforgiving environment makes the communities close-knit. But this time, when we walked in, girls sprang from their huts, the men from their farming chores and ran to greet us.

“Anteneh! Anteneh is back!” they yelled in Hamer, running to embrace him.

They treated us with a similar enthusiasm, and looked upon Ryan’s Western-style tattoos with a great curiosity. Throughout the days we spent with these people, we grew closer. Time passed and they forgot we were outsiders, forgot we were white boys from Lindsay. This is the best environment to make truthful portraits.

We’d spend the days sitting around with the girls, beading their clothing made out of goat skin, or with the men working the fields with a simple wooden plough attached to a bull. This kind of life brings truth to every “nobel savage” cliche imaginable, it really is the life. The Hamer share a connectedness to the earth that is mind-boggling for a Westerner to understand. To be in the midst of this, even just for a little while, is life changing. Damir, our cinematographer, got some great stuff and it was easy to forget he was there.

I grew particularly fond of a Hamer girl by the name of Omeleh. She told Anteneh she thought I was cute, and always came over to see what my straight hair felt like, how my camera worked, the weird clothes I wore, or the disgusting food I ate out of a bag. You don’t need to exchange many words to understand each other in these situations.

Now before this turns into a sappy story of forbidden love, I will stop and say that I had to keep my professionalism. I am still a visitor, and my actions ripple in great consequence. I didn’t want to make an escape in the middle of the night- “RYAN! RYAN! WE HAVE TO GO! RUN,” being chased by a band of angry potential Hamer grooms shooting AK’s at us. I was here to collaborate and appreciate the culture. All I will say is that when things get stressful and tough in New York, the first thing I usually think about is escaping to the Omo Valley, and training for the Bull Jump so I can get a Hamer bride. If I ever drop off the face of the earth, and you don’t hear a tweet out of me for years, you know where to look for me. Anteneh feels the same way and has a much stronger case. He is constantly having an internal struggle with himself as to whether he should continue to live in the city, or move back with the Hamer. It’s supporting his sisters through school that keeps him working for money and away from this village.

There came a night that was worth celebrating, so Ryan, Anteneh, Bali and I gathered 2 goats and a lot of honey wine stored in huge gourds. (This is an Ethiopian speciality, fermented from the honey of wild bees. Extremely potent when home-brewed.) The night was complete with a giant dancing circle. Everyone from the clan gathered in a huge circle around a fire dancing. The Hamer have a very erotic way of dancing and choosing mates. Basically a few men and women enter the circle at a time and face each other. The men makes thrusts in the air and leaps toward the woman. If the woman responds back, you may have yourself a girlfriend. If she doesn’t, you should try someone else.

I’ll never forget when Bali and Anteneh approached me and told me to come meet the elder women. I walked from the dancing over in the darkness to a group of 15-20 women sitting and chatting together. They put their hands on me. Anteneh explained they were thanking me for staying there. Meanwhile, I just wanted to thank them for accepting me, this was all too much.

Eventually we learned the words to Hamer songs. The pattern of one song is very interesting. Basically there is one lead vocalist you exclaims peoples names and the rest follow with a “shimba shimba!” This roughly translates to “, respect on you! respect on you!”

The Hamer then learned how to beat-box from us while I free-styled completely out of key over their beat. Why not share a little bit of our cultures music too? It was an amazing night I will never forget.

When it came time to leave, it was hard. Omeleh held my hand and didn’t want to let go.

THE DAASANACH

We left in the darkness of morning so we could reach our next destination in time- the Daasanach tribe.

It was difficult to cross the border into their territory. There is a government road block that checks your passports before passing. With the break out of armed conflict between Daasanach and Hamer, we were not permitted to spend much time there. We managed to convince the guard to let us in for the day only. I was upset at this, but happy we got the chance to go at all. In order to reach their village, it requires crossing the Omo River in a dug-out canoe.

I trekked into the village to find the chief while the rest of the guys waited by the riverside. I had taken most of my images last year by the Omo River, and I thought that would be a great place to set up the installation, putting the photographic prints in the same place that I took them one year earlier.

It was easy to convince the entire village to come down by the water when I showed them one print. This was never captured in video, but I remember feeling really badass walking out from the Daasanach village with a huge tribal mob behind me.

Balo, the beautiful Daasanach girl in one of my favorite portraits was all grown up now. She wasn’t the girly girl she was last year, she seemed very stoic and mature now. She will be married soon. When she turned over her print, she couldn’t look at it, she was too shy. She turned it to the crowd and smiled uncontrollably behind the protection of the masonite board.

One of my favorite print reactions of all time was one of the Daasanach chiefs, Ayi Techie. He looked at his print with a cocked eyebrow, then looked at Anteneh.

“Do I really look like this?”

“Yes! That’s you”

“Nah, too skinny”

Throughout the day he just sat quietly with his picture, looking at it like a very fussy art director.

We left Daasanach with high spirits, the prints had gone over well and the people were extremely grateful I brought them back. I know when I return again I will have their trust, and will be able to create more intimate portraits.

We returned the next day to Cascade River. She was still flooded, impossible to cross. We were running out of time, and we had to plan our days carefully. There was only one way to leave Turmi back to Arba Minch, which was via the long detour Jinka.

In secret I was happy about this, because I had a whole bunch of prints left over I wanted to deliver. The first was to a clan of Mursi.

THE MURSI

The Mursi are notorious for being difficult. They are extremely hostile and testy toward foreigners. They are intimating upon first sight- all covered in ghostly white powder, the women with their enormous lip disks, headdresses made of warthog bone, and always carrying weapons- whether it be a long pole for stick fighting, or an AK-47. Upon entrance to their land, it is mandatory that you take a government-appointed armed scout with you. The scout was a Mursi, so we trusted his knowledge of his own land.

Ryan, Anteneh and I are used to their tests. If they try to intimidate you, you just have to stand your ground and make a joke out of it. After all, they are human too.

The film crew was horrified after being poked to death, and huddled in the car not wanting to get out. After being pestered, Ryan and shoved a Mursi man back and shown him the long scar down his arm. (His bone ripped through is flesh in a bare-foot-water-skiing accident.) However in this land, a big scar means you have killed someone really important. The Mursi stopped, and gave an anxious laugh while throwing his arm around Ryan wanting to be friends.

Down the road into Mago National Park there are many “tourist villages” of Mursi. These are like Disney land, and where people looking for a “cultural safari” tend to flock. The people barely live in the traditional way, and will want to suck you dry of all your money just for taking photos. The Mursi I had photographed the year before were a more remote clan, located off the road, a trek through a little hillside overlooking an amazing view of Mago. These Mursi were kind and cool-headed.

When we arrived at the spot it was a ghost town. Nobody in sight, the huts sat abandoned. Our scout said there was a heavy drought earlier in the year, and because the Mursi are nomadic, the clan had moved and settled closer to the Omo River where the land was fertile.

He had no idea where that was. I showed the scout some of the prints, wondering if he personally recognized any of the faces. I told him the names of the people as he flipped through them… nope… nope… nope… Ah, then one. It was a woman named Engalo. The scout recognized her because during the drought she and her family had moved into the tourist village. This was not going to be easy.

We went into the most visited village and asked to speak to the chief. The chief was drunk and wouldn’t have any filming unless we gave him a lot of money. I understand payment, it’s normal and fair wherever you go. If you want to rent a location in New York, you have to pay for it. It should be the same in Ethiopia to benefit the local people. However the amount of money he was asking for was insane, and we simply didn’t have it left over in our budget. I told the crew that it didn’t matter if we got it on film or not, but I could just hand her the print and we could go.

Eventually the chief gave in to letting us walk Engalo to the car, give her the print filming only her, then leave. We did so, but Damir our cinematographer had pointed his camera all over the place (as he should have, a good operator gets lots of coverage) and now those Mursi wanted compensation. They swarmed us and got incredibly violent. It was time to leave. I walked toward the 4X4 in disappointment at the situation. But this was just the beginning.

A row of Mursi men lined up on the road with their guns, they meant business. We were not able to pass without paying more money. Anteneh has a reputation to keep as a guide in the Omo Valley, so I made the crew pay it to keep his good name with the Mursi. No matter what, I am always the visitor. I always have to live by the rules of the land the people set. It is not up to me to be upset or happy, I have to be passive and take the situation for what it was; study it. Learn from it.

THE JINKA MUSEUM

I had many unfound Mursi prints left over and the entire series of Hamer that we couldn’t get to because of the swollen river. There was no point in taking these all the way back to New York, I wanted them to go to good use. We decided to donate them to the Jinka museum. The curator was more than thrilled, and now they have a permanent home where everyone can appreciate and learn from them. The only thing I stress is that these are actually portraits of modern people living in the 21st century, and are in no way a museum artifact from the past. Now is the time to protect, preserve and explore these cultures before they disappear forever.

LET’S HIT THE ROAD, BOYS

And so, the long journey back to Addis began.

With of condition of the roads, our detour from Turmi took 2 days longer than expected. Helping pull other peoples trucks out of mud is a regular thing. When you see someone in need, you help them out… because next time it might be you. After a few hours of this, we got to stop in and visit the Arbore tribe.

THE ARBORE

This tribe has some of the most beautiful girls I’ve ever photographed in my life, period. The girls Rufo and Lago are my two favorite subjects, and of course Anteneh’s as well. I was done with the theatrics of revealing prints, in the Arbore tribe I just handed them off to the owners. When I approached Rufo with her print, she ran away in shock… Then took her time to come back and proudly take it from me.

I wanted to spend the night at the Arbore tribe so that we could get more footage and I could have the time to make more portraits. I got in one of the biggest fights of the entire trip with the director because he didn’t want to stay. Instead, we spent another night in a small concrete box, only hours away from the tribe. Why we decided to miss so many experiences is beyond me. Damir our cinematographer was sick, but still wanted to stay to get more footage.

At this point, it really got Ryan and I thinking about future episodes of the show. There’s a certain freedom I need in order to do what I do. My photo series trips do not run on a schedule, so it’s hard to have a time limit on things. However, I will say I am very proud of the way the documentary turned out in the end, and I think Blair did a fantastic job pulling it all together in the end. I had a great time, but with the film crew comes extra baggage. I admit I am difficult to work with myself, and I should be a little bit more open to them. I am a control freak because I am a photographer myself, and have a strict vision, so it’s just a struggle.

Eventually, we made it back to Addis. We spent a few days there unwinding, and repacking all the equipment for the plane ride.

When I go home, the memories of this country and it’s people are still everywhere around me- they are hung on my apartment walls in my own copies of the prints, and in the music I listen to that happened to be playing on those long drives. Leaving Ethiopia this time was easy- we missed our food from home and our own beds. It was leaving our friend Anteneh that was difficult. I promised him I’d see him again soon, and not to worry. Our little blue taxi cab pulled away toward the airport, and watched Anteneh get smaller and smaller, waving goodbye outside the window.

About 3 months later I landed a job in Dubai. The shoot got postponed by 2 weeks, so I hopped on the next flight and spend a week in Addis hanging out and getting in lots of trouble with Anteneh.

ADD A COMMENT (2)

Berry Jean // January 07, 2016 02:18

This was beautiful. I would love to work doing something similar. Inspiring

Royce R. Baucke // July 23, 2018 12:16

What a wonderful fascinating journey......I thankyou for sharing your story.....and I loved the way you returned to the people and delivered the prints to them....So many people TAKE but give nothing in return. I appreciate what I have seen here today.

Ka kite ano - arohanui oe.

Royce Baucke.

Your comment has been posted